I’ve spoken recently with several writers who are overwhelmed by their struggle to write intensely personal and emotional stories.

One has been hit by waves of emotion and fear because he finds himself feeling as if he’s reliving decades-old betrayal perpetrated by those closest to him. The writing has begun to feel like a prison keeping him locked in with ghosts of childhood trauma.

Another is so frightened by the possibility of exposure, he has transported his story across time and space and culture—jumping 200 years and 1,000 miles to write about a world that is almost completely foreign to him.

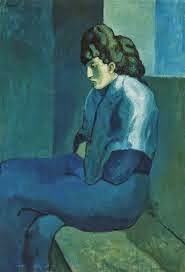

I’m no stranger to times when writing was difficult; I’ve named those my “writing crazy” periods. (Picasso had his blue period, right?) I was born anxious (maybe that’s why I wailed when the doctor pulled me out of my mother and into the world). Given certain tendencies of my nature and a creative life that includes many uncertainties, it’s no surprise I make occasional references to my various panic attacks and (mild) dissociative reactions, obsessions, acting out, and really very fleeting delusions. (I can say with confidence, however, that even in my darker periods, I never reached the point of molding tin foil hat-wear to block a) the radio waves sent by aliens or b) the attentions of a nagging feline with suspect intentions who parked on my sun roof.) I have spent serious time in my life delving inward to explore and understand as best I can my own psyche.

It’s nice to reach a place in life where details of my own creative struggles can be fodder for jokes. But when/if you find yourself writing material that elicits emotional backlash, that’s no joking matter.

I don’t believe that pushing “heroically” through emotional exhaustion and overwhelm serves the writer or the book or one’s mental health. And while writing can have therapeutic benefits, it can also take us to scary internal places. If the experience becomes overwhelming to the point where you question your ability to function normally, it is vital to reach out for support from a counselor, therapist, support group—so you can regain your sense of equilibrium and balance.

When I speak to writers, singly or in groups, I talk about the importance of taking time away from the intensity of writing, taking time to rest and breathe and find a place of balance where one can stay connected to the work without becoming overwhelmed. If you lose your sense of balance or your sense of humor, it’s definitely time to spend the day at the spa or a week at the beach or whatever suits your lifestyle and your budget.

If you lose your sense of humor, you risk your characters losing theirs as well. Readers crave and demand drama and they want to experience emotion; they want to be moved to tears and anger and laughter and forgiveness. They usually do not want to spend too much time with a character (you can also make that “writer”) who is exhausted, burned out, cranky, humorless, and depressed. (At least not unless that character is a foil and the rest of the book has a whole lot of comic relief.)

In order to give readers what they want—and provide deeply satisfying emotional experiences that pay off—the writer must reach a place where the narrative on the page has been processed so it’s not so raw, not so wrought that the writer isn’t able to consider the reader.

A quick rule for everyone (including writers): if you are feeling depressed, anxious, fearful, manic—to the point where you are not sleeping, eating, or functioning at “your normal”, reach out for help from a qualified mental health professional.

For some intensely personal narratives, the writer lives and writes in the place where emotion and detachment bump up against each other. I don’t believe there is any handy rule when it comes to proportions: two cups emotion and two and a quarter cups detachment? But you do need to reach a space where you can let go and have enough distance to consider the effect you want to achieve for the reader; and that is the space that allows you to revise effectively and make calculated editorial decisions and perhaps even bring humor to stories that might have seemed completely devoid of humor at the time.

A first draft tends naturally to elicit the wildest and rawest writing. That’s fine—as long as you know you can cope with the various waves of emotion that might be released internally. Writing should never endanger your mental health; it might be a way toward healing. Discomfort is okay; dysfunction is not.

You must always take care of yourself. If that means time off and away from the page, so be it! Our important stories do not go away just because we take breaks. But our ability to render those stories effectively increases when we live and love, learn, risk, replenish, and have fun.